About the map

The 1872 map of England & Wales was published by Edward Stanford, then of Charing Cross, London - still in business today as a vast map store in Long Acre, Covent Garden. It bore Price-William’s name for its authority and probably his authorship and remained in print for a few years, updated in 1874.

British Books in Print 1888

The map may have been an overprint of a pre-existing diocesan map. The 27 dioceses (at the time) of the Church of England are shown in a key at the base of the map. The original size was thought to be 72 x 84 inches, 1.83 x 2.13metres.

This edition of the map was originally cloth-backed and folded. The process involved dissecting the printed paper map into 120 separate sections and hand-mounting them onto a fine linen cloth, allowing small gaps for the folds. There is some mirroring of the print in the upper right caused by ink migrating to the adjacent sheets whilst folded.

Exploring the map

To explore the map in general, click the button to open the interactive R. Price-Williams map in a new tab.

The links in the detail sections below open the map zoomed and centred on that location.

RailMapOnline.com is also useful as a reference to the railways that were eventually built.

Processing the map

This copy is held by Stanford University Library. They have cut the map into quarters, mounted each quarter onto flat card and digitised each section at 600dpi. The resulting digital images are each approximately 23,000 x 27,000 pixels. The alignment of the digital images is slightly off.

Timetable World has attempted to crop and join the four pieces together, not entirely successfully. The south-east quarter is still misaligned by approximately 0.6° but most software tools struggle with such huge files. The longer-term aim is to geo-locate the map, section by section, which would allow it to be compared with contemporary maps and would handle any alignment issues. The maths is involved is rather challenging.

Richard Price-Williams

Richard’s father John Morgan Williams was a surgeon who spent most of his life at Bridgend in South Wales. However, Richard and some of his siblings were born in Stoke Newington, a suburb of north London in 1828. He was fourth of nine children. The family were landowners in Wales and Richard spent much of his childhood in Wales.

His younger brother Arthur John Williams became a lawyer and a radical Welsh Liberal Member of Parliament. He wrote widely, including in 1868 “The Appropriation of the Railways by the State”.

Richard’s nephew Eliot Crawshay-Williams, Arthur’s son, also became an MP. Crawshay-Williams wrote to Churchill in 1940 during Britain’s “darkest hour”: "I'm all for winning this war if it can be done," the letter said, adding that "an informed view of the situation shows that we've really not got a practical chance of actual ultimate victory" and that "no questions of prestige should stand in the way of our using our nuisance value while we have one to get the best peace terms possible.". Churchill's reply was blunt: "I am ashamed of you for writing such a letter. I return it to you -- to burn and forget."

As for Richard, he became an engineer. He served a pupillage under George Heald, who was Thomas Brassey's engineer on the construction of the Lancaster, Carlisle, and Caledonian Railways in 1845-6. He afterwards served as an apprentice in the locomotive works of Messrs. Kitson, Thompson and Hewitson at Leeds, being engaged later on, from 1854 to 1860, in designing and preparing plans of girder bridges, and carrying out other works while resident engineer at Leeds on the Great Northern Railway. Subsequently he acted as Consulting Engineer for the proposed Metropolitan Outer Circle Railway, and in the preparation of plans and estimates for several other railways, both in the UK and in the Empire.

He wrote and presented several papers to the Institute of Civil Engineers from the 1860s onwards and had “The Maintenance and Renewal of Permanent Way” published in 1866. His reputation was founded upon a partnership with the inventor Henry Bessemer. Bessemer had developed a process in the early 1850s for mass-producing steel, and Price-Williams promoted the use of steel rails in place of cast iron. He was put in charge of Bessemer’s first steelworks in Greenwich, and then moved in 1862 to Bessemer’s Stocksbridge plant, north of Sheffield, where a specialised rail mill was installed.

He married Jane Blackwood Dunlop in 1864, and they had eight children. They may have been resident in Ardwick, Manchester – across the Pennines - where she was from, and where the first two children were born. But by the mid-1860s they were living back in Greenwich. Commuting Ardwick to Deepcar (for Stocksbridge) was certainly possible: Bradshaw's 1877

Price-Williams also wrote for the Royal Statistical Society on the economics of railway construction and became a vice-president in later life. His writings were often referenced in the engineering press. He was appointed by the Royal Commission on Coal Supplies in 1866 and subsequent years to prepare evidence of their duration, and for the Royal Commission on Irish Railways in 1868 he was appointed Chief Engineer to examine and value them. He also acted for most of the principal railway companies in the United Kingdom to prepare and advocate their claims against the Government for the purchase of the telegraphs in 1871.

In 1889 he reported upon the condition of the railways in New South Wales and Tasmania, and afterwards acted as arbitrator on behalf of the Tasmanian Main Line Railway Co. for the disposal of the railway to the Tasmanian Government, being subsequently appointed Consulting Engineer by the Governor.

He became a Member of the Institution of Civil Engineers in 1861, and was awarded the Telford, Watt, and Stephenson gold medals. The Iron and Steel Institute awarded him the Bessemer gold medal in 1898 on the recommendation of Sir Henry Bessemer.

He died at Bournemouth on 19th September 1916.

Shropshire

Abraham Darby's 1776 bridge at Ironbridge, Shropshire. © Ironbridge Gorge Museum

Zoom to Shropshire: R. Price Williams map | RailMapOnline

Shropshire was one of the earliest regions to experience the Industrial Revolution but did not grow as much as other regions. Abraham Darby discovered how to use local supplies of coal, rather than wood-based charcoal, to smelt local iron, and built the first iron bridge in 1776.

The railway network in the county was essentially complete by 1872. Shropshire had small pockets of coal in various places but lacked the scale of other regions to underpin the development of major industrial centres. Many lines had been authorised that were not progressed. These included:

- The Potteries, Shrewsbury and North Wales Railway opened in 1866 from Shrewsbury westwards, but was closed by 1880. The authorised link north-east to Market Drayton was never progressed. The line was reopened in 1911 by Colonel Stephens as a light railway and subsequently came into its own during World War 2 as the artery for the Nescliffe ammunition depot. A spur to the Nesscliffe sandstone quarries was not progressed

- The Bridgnorth, Wolverhampton and Staffordshire Railway was authorised in 1866 but money could not be raised

- The Bishop's Castle Railway in the south-west of the county had ambitions to connect with Minsterly and Montgomery. The company went into receivership in 1867 - and stayed there for 69 years - leaving trains to reverse at what should have been Lydney Junction.

Norfolk

Yarmouth Beach railway station being demolished (1959)

Zoom to Norfolk: R. Price Williams map | RailMapOnline

Norfolk perhaps displays the opposite characteristics of Shropshire. In 1872, large parts of this rural and sea-facing county had no rail links and only a short link to North Walsham had been authorised. It was, perhaps complacently, seen as “Great Eastern” territory. Yet over the following 20 years, the situation was transformed by the extension of the Midland & Great Northern Railway, reaching in from King’s Lynn in the west and avoiding the county town of Norwich.

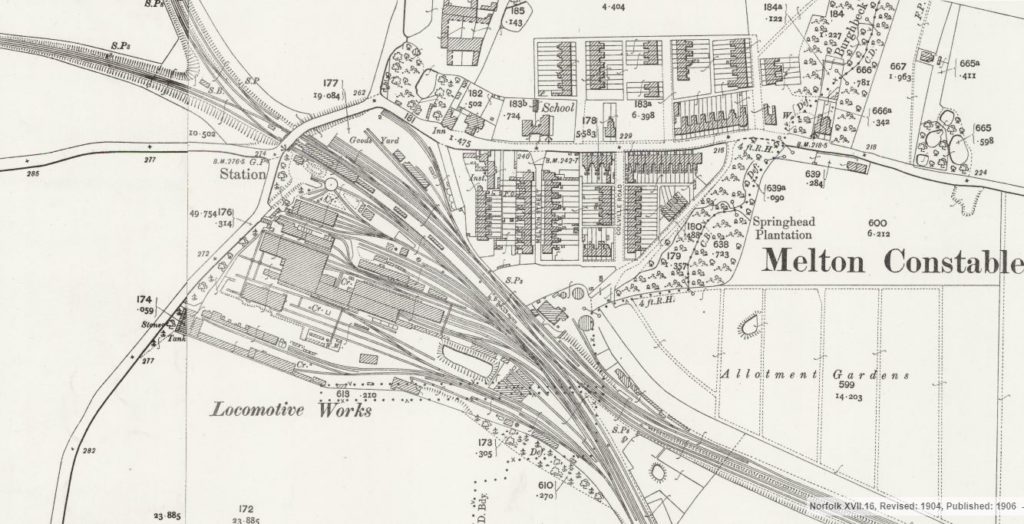

The new line had to create much of its own traffic. The coastline was promoted to holidaymakers of the East Midlands; towns like Cromer developed and many villages added “on-Sea” to their names. Great Yarmouth and Lowestoft were tapped for their vast fishing industries, and Melton Constable went from tiny hamlet to major junction – and back again after closure in 1959.

The Great Eastern developed only a little more north of Norwich and there was some cooperation with the M & GN, running two costal routes jointly.

Melton Constable - Junction, Railway Works - 1904 Map